Blavatsky News

An informative site for those with an interest in Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

Thursday, December 4, 2014

Blavatsky News

* Wendy Doniger reviews the latest release in the Princeton University Press series Lives of Great Religious Books: The Bhagavad Gita: A Biography by Richard H. Davis. Doniger draws attention to Davis’s narrative of the rise of the Gita as the Bible of India and the book’s subsequent appeal to the Western world. Both accounts leave out the Theosophical contribution, with inexpensive editions of The Bhagavad Gita by W. Q. Judge and Annie Besant published by the Society in the 1890s, and the Theosophists’ allegorical approach. Readers looking for that information will have to rely on Catherine A. Robinson’s 2006 Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita and Images of the Hindu Tradition: The Song of the Lord, which draws on Eric J. Sharpe’s The Universal Gita: Western Images of the Bhagavad Gita a Bicentenary Survey from 1985.

* Typeset In The Future, a site dedicated to fonts in sci-fi, devotes a post to the typography in the 1979 movie Alien. Looking at the keyboard used in the film, the writer points out certain novel features, such as keys marked “PRANIC LIFT 777” and HUM”:

designer Simon Deering needed some complex-sounding labels for the keyboard at short notice. He was reading The Secret Doctrine by Helena Blavatsky, a Russian philosopher and occultist, at the time of filming. Blavatsky's book attempts to explain the origin and evolution of the universe in terms derived from the Hindu concept of cyclical development. Deering found his inspiration in its pages, and the Nostromo’s odd keyboard was born.

A list of References to Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine in the movie Alien is given at Alien Explorations, a site “Exploring the ‘Alien’ Movies”.

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Nehru and Theosophy

On a visit to the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi, Ian Smith was surprised to see the reference to Jawaharlal Nehru’s involvement with Theosophy.

One thing I hadn’t known was that the young Nehru had links for a time with the esoteric philosophy of Theosophy, popularised by Helena Blavatsky in the late 19th century. His boyhood tutor Ferdinand T. Brooks got him interested in it and he was initiated into the Theosophical Society at the age of 13 by the versatile Annie Besant, a friend of the family who wasn’t just a Theosophist but also a writer, socialist, women’s rights activist, supporter of home-rule for Ireland and India, and member (and later president) of the Indian National Congress. Here’s a wall-display that’s dedicated to her.

Nehru’s involvement with Theosophy is covered in Michael Gomes’ “Nehru Theosophical Tutor” published in Theosophical History, vol. 7, no. 3, July 1998. It looks at the career of his tutor, F.T. Brooks, who influenced his interest in Theosophy.

Of his time among the Theosophists, Nehru writes in his Autobiography:

I have a fairly strong impression that during these theosophical days of mine I developed the flat and insipid look which sometimes denotes piety and which is (or was) often to be seen among theosophist men and women. I was smug, with a feeling of being one-of-the-elect, and altogether I must have been a thoroughly undesirable companion for any boy or girl of my age.

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Blavatsky and the Harlem Renaissance

Forthcoming from Brill in 2015, Esotericism in African American Religious Experience: “There Is a Mystery”, edited by Stephen C. Finley, Margarita Simon Guillory, and Hugh R. Page, Jr., makes a major contribution to the new area of Africana Esoteric Studies (AES): a “trans-disciplinary enterprise focused on the investigation of esoteric lore and practices in Africa and the African Diaspora.” The book’s twenty essays cover a number of African American cultural trends from the nineteenth century to the present.

Jon Woodson’s chapter, “The Harlem Renaissance as Esotericism,” looks at the influence of Blavatsky on one of the key figures in the Harlem Renaissance, Jean Toomer:

It is often said that there was an occult revival in the 1920s and that the occult revival was prepared by the popularity of theosophy, a movement that began in the nineteenth century and that continued to be influential as modern cultural movements began to form. The founder of Theosophy, H.P. Blavatsky was a prolific author whose books were widely disseminated by the Theosophical Society. Jean Toomer, the central figure in the introduction of esoteric thought into the African American community in the 1920s, had a deep appreciation for Blavatsky’s writings and he used her concepts to originate his revision of racial thought.

Toomer (1894—1967), an important figure in African-American literature, became a conduit for esoteric ideas to his circle that included Carl Van Vechten and Zora Neale Hurston. He later became interested in Gurdjieff, studying with A.R. Orage in America and travelling to France to meet Gurdjieff. According to Woodson, “The attraction of Blavatsky for Toomer was the authority with which she explicated the various stages of man's rise from the material to the ethereal.”

The volume also contains a chapter on “Paschal Beverly Randolph in the African American Community” by Lana Fineley.

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Blavatsky and the Nazis

We have often wondered why Theosophists don’t take a more active role in the defense of their Founder, H. P. Blavatsky. The Internet has become a lawless frontier when it comes to accuracy about her. In our era the most pernicious charge against Blavatsky is that she was somehow responsible for an occult influence on the Third Reich and subsequent avowals by prominent Nazis. The claim on its face shows a lack of awareness of German culture. Nazis did not need Blavatsky for anti-semitic ideas; Martin Luther had already provided it. Léon Poliakov's The Aryan Myth: A history of racist and nationalist ideas in Europe, available in English since 1974, long ago showed the real sources of this idea. Yet fictions are often more welcomed than facts.

So we are happy to see the subject addressed by Carlos Cardoso Aveline, who usually spends his time pointing out the foibles of other Theosophists. “Blavatsky, Judaism and Nazism: Message to an Author Who Did Not Study Theosophy” takes aim at the usual mentions of Blavatsky in connection with this subject:

You fail to see that the first and most important object of the theosophical movement is anti-Nazi. It establishes that all men and women of whatever race or caste, ideology or nation, are equal in rights and in brotherhood. This, main object of the movement is “To form a nucleus of a Universal Brotherhood of Humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color”.

You mention the svastika symbol of theosophical movement (which was founded in 1875). The svastika is Hindu. It is a most ancient symbol for the Kosmic evolution, and it is not a Nazi symbol, therefore. The Nazis misused it for their own anti-evolutionary purposes, and this is their karma.

His itemized list is worth reading and can be found here. Steven Otto’s “Liar, Racist, Antisemite, Satanist and Nazi!” can also be added to the literature countering the racism allegations, Nazi accusation, and Anti-Semitism brought against Blavatsky. As can the entry on the subject by the Blavatsky Theosophy Group UK here. These contributions offer a well-reasoned response by those who have actually read what Blavatsky wrote and deserve wider recognition by all who have an interest in a more accurate image of H. P. Blavatsky.

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Blavatsky News

* The website of the International Gothic Association, which unites “teachers, scholars, students, artists, writers and performers from around the world who are interested in any aspect of gothic culture,” looks at Blavatsky in the light of Victorian culture. In ‘“I was sent to prove the phenomena and their reality”: The Gothic Madame,’ Miss Jamie Spears suggests that “If Madame Blavatsky had not lived, Victorian Gothicists would have invented her.”

So, why would the Gothicists of her time have invented her? Blavatsky is, in effect, the perfect storm of societal transgression. Her life represents a catalogue of Victorian social anxieties and fears concerning the conduct of women. Though she never self-defined as one, she exemplifies the New Woman movement in her refusal to surrender her own agency and will to that of men.…It is relatively easy to imagine a character such as hers being dreamt up by an anxious, social-conservative writer at the end of the 19th century: a female immigrant who sought to revolutionise British religious practice was, for many, the stuff of nightmares.

* Under the listing of Blavatsky’s Travels, Google Maps shows the places mentioned in Blavatsky’s Caves and Jungles of Hindustan written in the 1880s, starting in Mumbai (then Bombay) and ending in Allahabad. For most of her life, H.P. Blavatsky supported herself by writing lightly fictionalized accounts of her travels in India for Russian papers.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

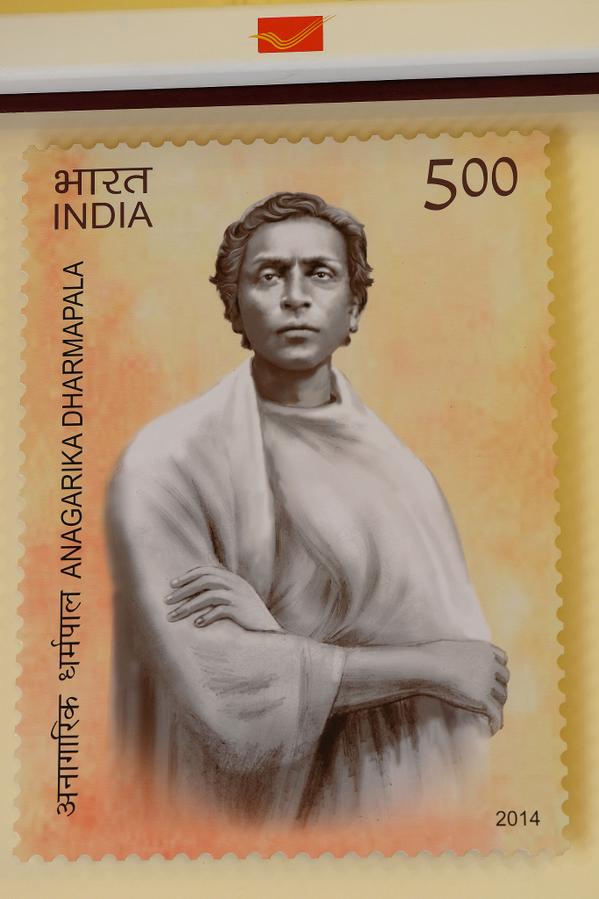

Anagarika Dharmapala

The President of India’s Twitter feed announces the release of a new stamp honouring Sri Lankan Buddhist Anagarika Dharmapala. “The release of the commemorative postage stamp on Anagarika Dharmapala will contribute towards further strengthening the bilateral ties between India and Sri Lanka and bring the two nations closer,” said President Mukherjee.

Reporting on the occasion a number of South Asian news sources mentioned: Along with Henry Steel Olcott and Helena Blavatsky, the creators of the Theosophical Society, he was a major reformer and revivalist of Ceylonese Buddhism and an important figure in its western transmission.

Events celebrating the 150th anniversary of Dharmapala’s birth were held in England and Sri Lanka in September. In London, An Exhibition on the Life and Work of Anagarika Dharmapala, Founder of London Buddhist Vihara, was held from September 14 to 20, 2014. Over the seven days guests included the Mayor of Ealing, the UK Sri Lanka High Commissioner, and the President of the Buddhist Society among others. In Sri Lanka a stamp was also issued commemorating his anniversary.

Previous coverage of Dharmapala (1864-1933) and his connection with Blavatsky can be found here. Steven Kemper’s Rescued from the Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala and the Buddhist World, the first book length study of his career, to be released next month by the University of Chicago Press, will no doubt bring him renewed recognition. According to the publisher’s press release:

Drawing on huge stores of source materials—nearly one hundred diaries and notebooks—Kemper reconfigures Dharmapala as a world-renouncer first and a political activist second. Following Dharmapala on his travels between East Asia, South Asia, Europe, and the United States, he traces his lifelong project of creating a unified Buddhist world, recovering the place of the Buddha’s Enlightenment, and imitating the Buddha’s life course. The result is a needed corrective to Dharmapala’s embattled legacy, one that resituates Sri Lanka’s political awakening within the religious one that was Dharmapala’s life project.

Chapter 1 deals with Dharmapala as a Theosophist.

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Blavatsky and Mexican Politics

A Mexican President may not seem a likely reader of Blavatsky but journalist C.M. Mayo has shown this was the case with Mexico’s 33rd President Francisco Ignacio Madero (1873‒1913):

Francisco Ignacio Madero was the leader of Mexico’s 1910 Revolution and the democratically elected President of Mexico from 1911 until 1913, when, in a violent coup, his government was overthrown and he was murdered. Today Madero is best remembered as the “Apostle of Democracy,” the visionary leader who overthrew Porfirio Díaz, the dictator who had ruled Mexico, both directly and indirectly, for more than three decades.

Less known is that Madero was also one of Mexico’s leading Spiritists and a medium. Not only did he maintain an extensive correspondence with Spiritists in France and Mexico, but he was a organizer of Latin America’s first and second Spiritist Congresses held in Mexico in 1906 and 1908, respectively, and it was after the latter that he took upon himself the task of writing and publishing the ardently evangelical Spiritist Manual, albeit under the pen name, “Bhima.”

In her new book, Metaphysical Odyssey Into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual, Mayo gives a rare glimpse into the esoteric world that flourished in Spain and in Mexico in the early part of the 20th century.

In the late 19th century, though elite Mexicans more often traveled to, studied in and had business dealings in the Unted States, they tended to feel more comfortable with French language and culture. Unsurprisingly then, it was Kardecian Spiritism, rather than American Spiritualism, that first made inroads in Mexico. This was in 1872, thanks to Refugio González's translations of Kardec’s books, among other Spiritist works.

During this same period, the Russian mystic and co-founder of Theosophy, Helena Petrovna Blavatksy (1831-1891) published her seminal works, Isis Unveiled (1878) and the Secret Doctrine (1888), which were almost immediately translated into French and which infused Western esoteric thinking, including that of some of the Spiritists, with new strains of Eastern and neopagan thought.

Mayo’s findings after months spent going through Madero’s library in Mexico City offer an indication of the diffusion of these ideas outside the Anglo-European grid. The latter part of the book contains her English translation of Madero’s 1911 Manual Espírita, his attempt to fuse spiritist and theosophical ideas published under the name Bhima. More information about the book and an interview with the author commenting on the mixing of European esotericism and Mexican beliefs can be found here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)